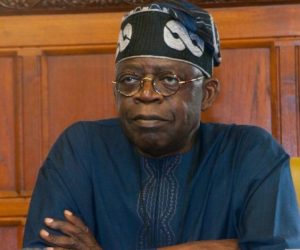

IT is a truism that a country’s foreign policy is the reflection of its domestic circumstances. A country that faces huge economic, political and security crises at home would be foolhardy to prosecute a war abroad. Furthermore, a robust foreign policy depends on domestic support. Thus, it’s utterly reckless and dangerous for a president to take his country into a foreign war without the endorsement of the legislature and understanding of critical domestic constituencies! Yet, that’s what Bola Tinubu, Nigeria’s new and sophomoric president, seems intent on doing in response to the military coup in Niger Republic.

Since the coup in July, which removed President Mohammed Bazoum from power and installed General Abdourahamane Tchiani as head of state, Tinubu has talked tough, vowing that “all means will be used to restore constitutional order in Niger”. Under his leadership as chairman of the Economic Community of West African States, ECOWAS, the organisation gave the junta a week’s ultimatum to reverse the coup. When that failed, ECOWAS ordered the “deployment” of a “standby force” to invade Niger. Now, it’s said to have agreed a “D-Day” for military action!

Meanwhile, Nigeria has imposed stringent economic sanctions on Niger. First, it cut power supply to Niger, which depends on Nigeria for over 70 per cent of its electricity. Second, Nigeria closed its borders with Niger. But a key test of economic statecraft is that it must be effective and not result in self-inflicted economic costs. Yet, the sanctions on Niger have, so far, failed that test: they have not reversed the coup and have harmed Nigeria.

Economic sanctions tend to hurt ordinary citizens in the targeted country and turn them against the imposer. That’s what has happened in Niger where ordinary Nigeriens have rallied behind the junta and against Nigeria, ECOWAS and meddling Western countries like France and the United States. Furthermore, evidence shows that the seven Northern Nigerian states that share borders with Niger are incurring huge economic losses due to the border closure. Clearly, Nigeria is hurting itself by purporting to be punishing Niger. Given that Hausa, a major Nigerian ethnic group, makes up more than half Niger’s population, Nigeria is, indeed, unwise to impose sanctions, and consider war, on Niger!

But the foregoing raises two questions. First, why is war with Niger in Nigeria’s national interest, when insecurity ravages Nigeria, when just last week 36 Nigerian soldiers were killed during an ambush by armed gangs in Niger State? Second, why is war with Niger a priority for Tinubu, who is barely three months in office and faces monumental governance and leadership challenges at home?

Take the second question first. Truth be told, Tinubu is a very weak president who lacks overwhelming domestic support. He came to power through a controversial election and with a minority share of the popular vote, rejected by 63 per cent of the voters. As I write, everyone awaits the verdict of the Presidential Election Petition Tribunal, PEPT, on his election, and the matter will eventually go to the Supreme Court. Technically, Tinubu could be removed from office. For a president in such circumstances to be contemplating a foreign war in less than 100 days in office really rankles. Inevitably, Tinubu’s warmongering has triggered speculations about his real motivation. Someone cynically suggested that he wanted to declare a state of emergency so as to derail the election petitions. I doubt it! But how could Tinubu take such a reckless gamble? He wrote to the Senate asking for approval to send Nigerian soldiers to invade Niger, ignoring the fact that the far North, whose votes made him president, would never support war against Niger, with which they share centuries-old historical and cultural ties. So, unsurprisingly, influenced by the views of Northern senators, the Senate rejected his request. He ignored the domestic constraints, failed to assess the situation carefully, and suffered an embarrassing foreign policy defeat! Which brings us to the broader question: Why is war with Niger in Nigeria’s national interest? Under international law, a country could use force against another on the ground of self-defence or reprisals. Neither exists here. The coup in Niger poses no imminent threat to Nigeria’s security. So, the only possible excuse is the defence of democracy. But that’s utterly unconvincing. If, God forbid, there’s a coup in Nigeria, could ECOWAS threaten the junta? No, because “might is right”! And what about the three ECOWAS countries under military rule before Niger, when would ECOWAS force attack them? Never! So, why Niger?

In any case, what’s democracy? In his book Enemies of Society, Paul Johnson argues that the true essence of democracy is “the ability to remove a government without violence, to punish political failure by votes”. But if that’s impossible because of rigged elections and tenure elongation, as common in West Africa, is that democracy? Militarism thrives on political instability, the antidote is credible elections, good governance and an independent judiciary that can right wrongs.

Truth is, military intervention is not the answer to the coup in Niger, but diplomacy and sensitivity to the wishes of Nigeriens. Thus, Tinubu’s strongman, macho politics is misguided, reckless!

DailyrecordNg …Nigeria's hottest news blog

DailyrecordNg …Nigeria's hottest news blog